Introduction

Most backend codebases don't start broken. They start small, coherent, and easy to change. Then time passes.

Features ship. Teams grow. Deadlines happen. And one day you realize that changing the checkout flow requires touching seven packages, three shared utilities, and a database table that four other features depend on. You're not sure what will break, so you test everything manually and deploy on a Friday afternoon with your finger hovering over the rollback button.

This is two problems working together. Low cohesion: related code is scattered across the codebase instead of living together. High coupling: unrelated modules depend on each other's internals, so changes ripple outward in unpredictable ways.

When it gets bad enough, teams usually respond in one of two ways.

Some reach for microservices. Split everything into separate services. Coupling becomes impossible because nothing can import anything directly. But this trades code complexity for operational complexity: network failures become normal failures, data consistency requires careful choreography, and "running locally" becomes a research project. You wanted to fix your architecture and accidentally became a distributed systems team.

Others try better discipline. Add architectural guidelines. Improve folder structure. Be more careful in code review. This is cheaper and less disruptive—but discipline erodes. Someone imports an internal class because it's convenient. Someone adds a "temporary" dependency to meet a deadline. Guidelines without enforcement are aspirations.

A modular monolith is a way to make the second approach actually stick. It's a monolith where boundaries are enforced by the build system—where you can't import another module's internals because the compiler won't let you.

You keep the operational simplicity of a single deployable. But you get real architecture: explicit contracts between modules, isolated data, and the ability to change one module without accidentally breaking others. When something goes wrong at 3am, there's one service to check, one log to read, one thing to restart.

This guide is a practical walkthrough of building one in Kotlin and Spring Boot. I'll cover where to draw boundaries, how to enforce them with Gradle, how to structure code inside modules, how to isolate data, how modules communicate, error handling, and testing. The focus is on patterns that work in real codebases—things I've learned building systems this way, not theoretical ideals from a whiteboard.

Part 1: Where to Draw the Lines

We want boundaries. But where should they go?

Domain-Driven Design has opinions about this. DDD has a reputation for academic terminology and books thicker than your laptop, but ignore all that—the part that matters for architecture is simple: organize around business domains, not technical layers.

Domains, Not Layers

Most backend projects start with a structure like this:

com.example.app/

├── controllers/

│ ├── ProductController.kt

│ ├── OrderController.kt

│ └── ShippingController.kt

├── services/

│ ├── ProductService.kt

│ ├── OrderService.kt

│ └── ShippingService.kt

└── repositories/

├── ProductRepository.kt

├── OrderRepository.kt

└── ShippingRepository.kt

All controllers in one folder, all services in another, all repositories in a third. It feels tidy. It looks professional in code review.

It's also a mistake.

When you add a shipping feature, you touch files in three different folders. When you want to understand how shipping works, you're jumping between layers, assembling the picture from scattered pieces. And nothing stops OrderService from calling ProductRepository directly—the folder structure creates the appearance of organization without any actual boundaries.

The alternative is organizing by domain:

com.example.app/

├── products/

│ ├── ProductController.kt

│ ├── ProductService.kt

│ └── ProductRepository.kt

├── orders/

│ ├── OrderController.kt

│ ├── OrderService.kt

│ └── OrderRepository.kt

└── shipping/

├── ShippingController.kt

├── ShippingService.kt

└── ShippingRepository.kt

Now a shipping/ folder contains everything about shipping. New developers can open one folder and understand one capability. Changes stay local. And the structure reveals where real boundaries could be enforced.

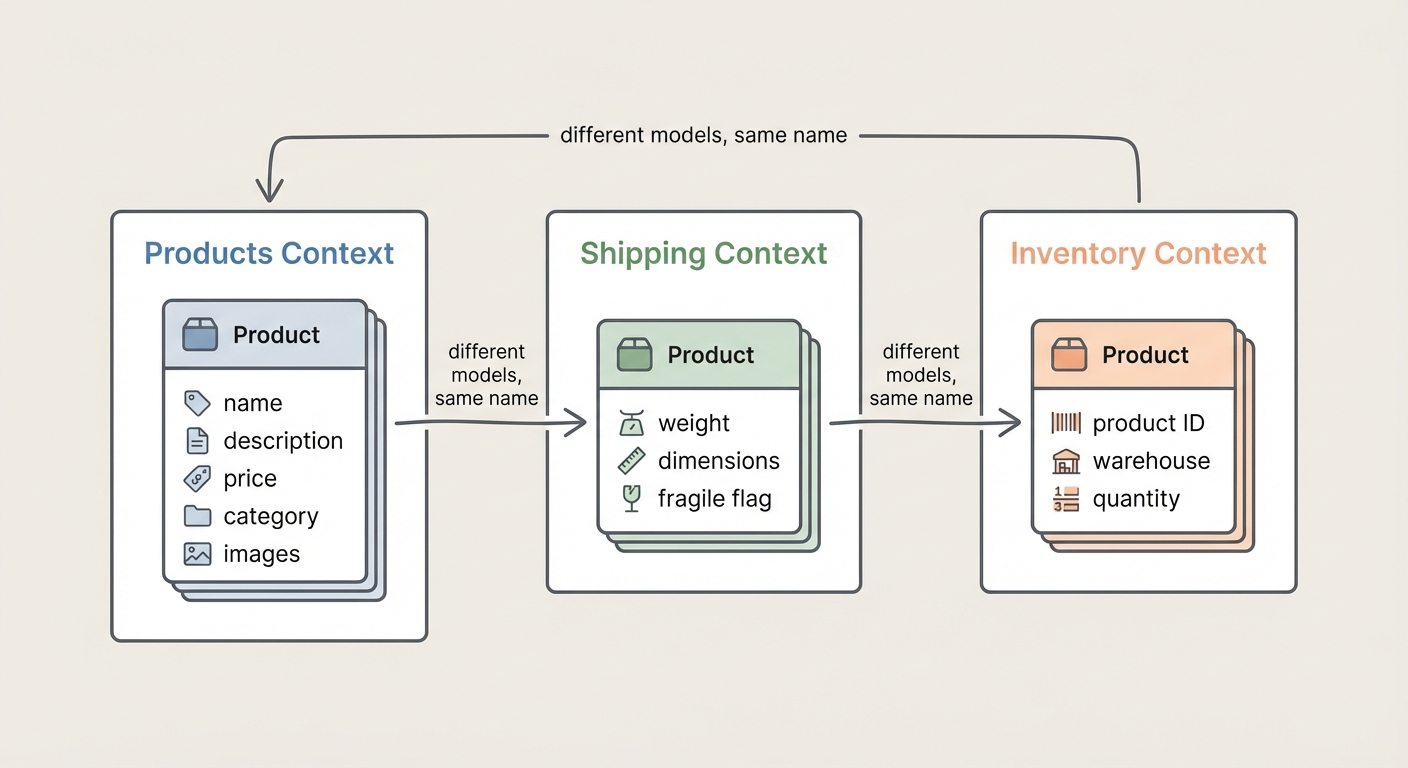

The Same Word, Different Meanings

Ask three people in an e-commerce company what "Product" means:

The catalog team says name, description, price, images, sustainability rating—it's what customers browse and search. The warehouse team says weight, dimensions, and whether it's fragile—they need to put it in a box, not describe it. The inventory team says a product ID and a quantity on a shelf—they don't care what it looks like.

These aren't three views of the same thing. They're three different concepts that happen to share a name. DDD calls this a bounded context: a boundary within which a term has a consistent meaning. You can call it whatever you want. The point is that "Product" means something different depending on who you ask.

The instinct is to create one Product class that serves everyone:

data class Product(

val id: ProductId,

val name: String,

val description: String,

val price: Money,

val images: List<Image>,

val sustainabilityRating: String,

val weightGrams: Int,

val dimensions: Dimensions,

val isFragile: Boolean,

val warehouseQuantities: Map<WarehouseId, Int>,

// ... and it keeps growing

)

One class, no duplication—efficient, right? But this is how coupling starts. The catalog team adds images; now warehouse code depends on it. The warehouse team adds dimensions; now catalog code carries that weight. Everyone's afraid to touch this class, and everyone has to.

The fix is recognizing that each context should define its own model:

// In the catalog context

data class Product(

val id: ProductId,

val name: String,

val description: String,

val price: Money,

val images: List<Image>,

)

// In the shipping context

data class ShippableItem(

val productId: ProductId,

val weightGrams: Int,

val dimensions: Dimensions,

val isFragile: Boolean,

)

Yes, you now have two classes with some overlapping fields. This feels wasteful until you realize the alternative is a God object that grows until it collapses under its own weight. Duplication between contexts is healthy. Duplication within a context is a code smell. Learn the difference.

Finding the Right Boundaries

There's no algorithm for this, but there are useful signals.

Listen for different vocabulary. When warehouse staff say "pick" and "pack" while marketing says "browse" and "wishlist," you're hearing two contexts. Language differences usually reflect model differences—this is more reliable than most technical heuristics.

Different rates of change are another clue. Pricing rules might change weekly; shipping carrier integrations change quarterly. Bundling them means every pricing change risks breaking shipping. And if different people are responsible for different areas, those are natural seams. Conway's Law isn't just an observation—it's a force you can work with instead of against.

Transaction boundaries help too. If two operations almost always happen together in the same database transaction, they probably belong together. If they don't need transactional consistency, that's a hint they could be separate. Conversely, if module A makes fifteen calls to module B for every operation, maybe they shouldn't be separate at all.

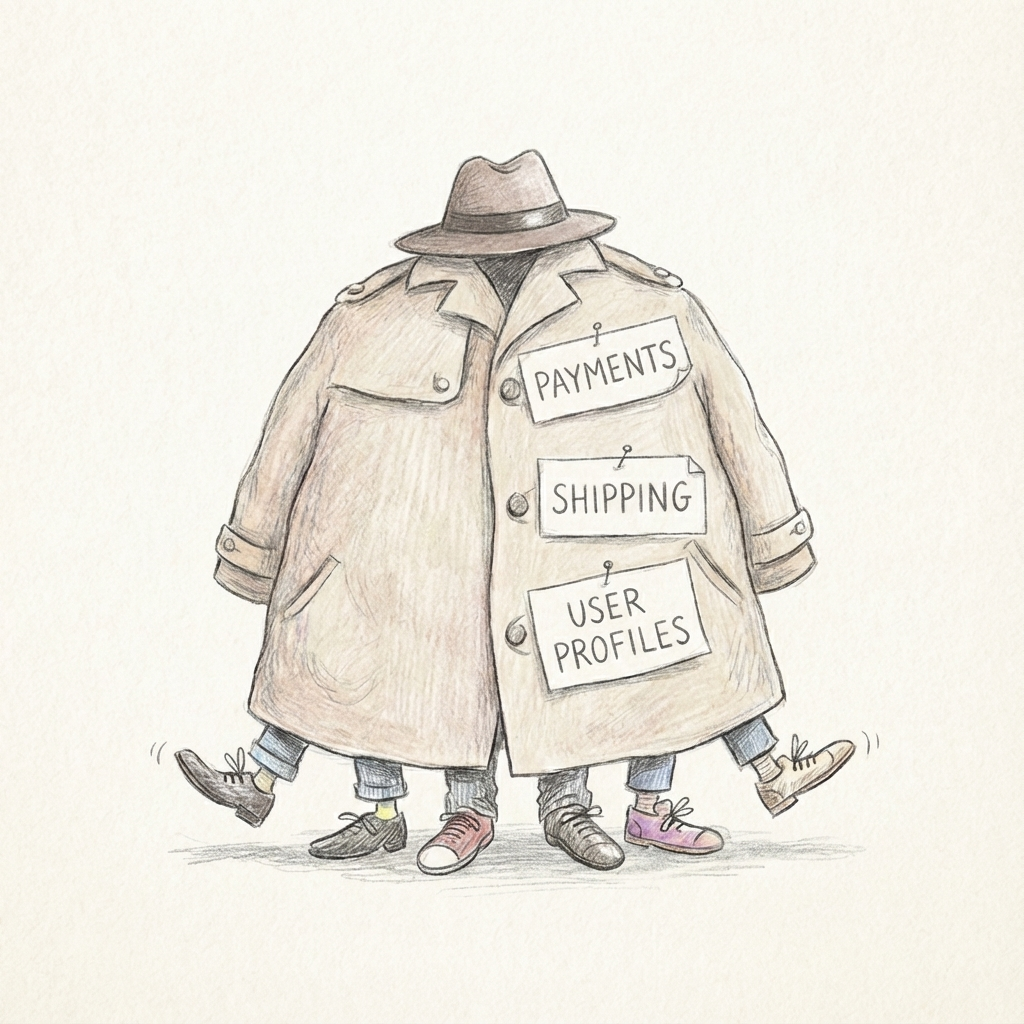

Size matters. Can you describe the module in one sentence without conjunctions? "Manages the product catalog" works. "Handles payments and shipping and user profiles" is three modules wearing a trench coat.

Watch out for a few traps. Don't model from the database up—tables reflect storage decisions, not business boundaries. Don't share entities across contexts just because it feels DRY; if you're adding fields that only one context uses, you've got coupling. Don't slice too thin—you don't need a separate module for "OrderValidation," that's just part of orders. And don't draw boundaries that cut across team ownership. The best technical boundary won't help if nobody knows who's responsible for it.

The Example We'll Use

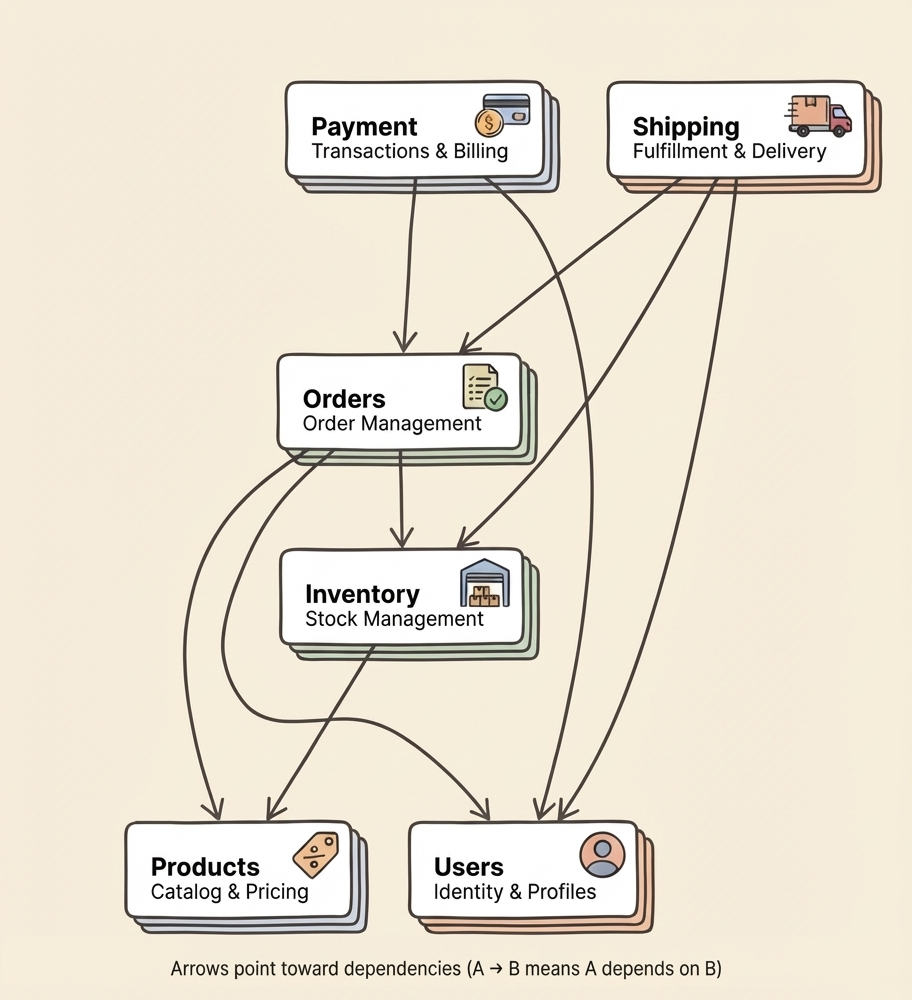

For this guide, we're building an e-commerce system with four bounded contexts:

Products owns the catalog—names, descriptions, prices, images. Orders handles purchases and their lifecycle. Shipping manages fulfillment and delivery. Inventory tracks what's in stock and where.

Orders depends on Products (needs to know what's being ordered) and Inventory (needs to check availability). Shipping depends on Orders (needs to know what to ship) and Products (needs weights and dimensions). Nobody depends on Orders—it's a leaf in the dependency graph.

These boundaries aren't perfect. We'll discover friction as we build. That's fine—the enforcement mechanisms in the next section make refactoring boundaries a manageable task rather than an archaeological expedition.

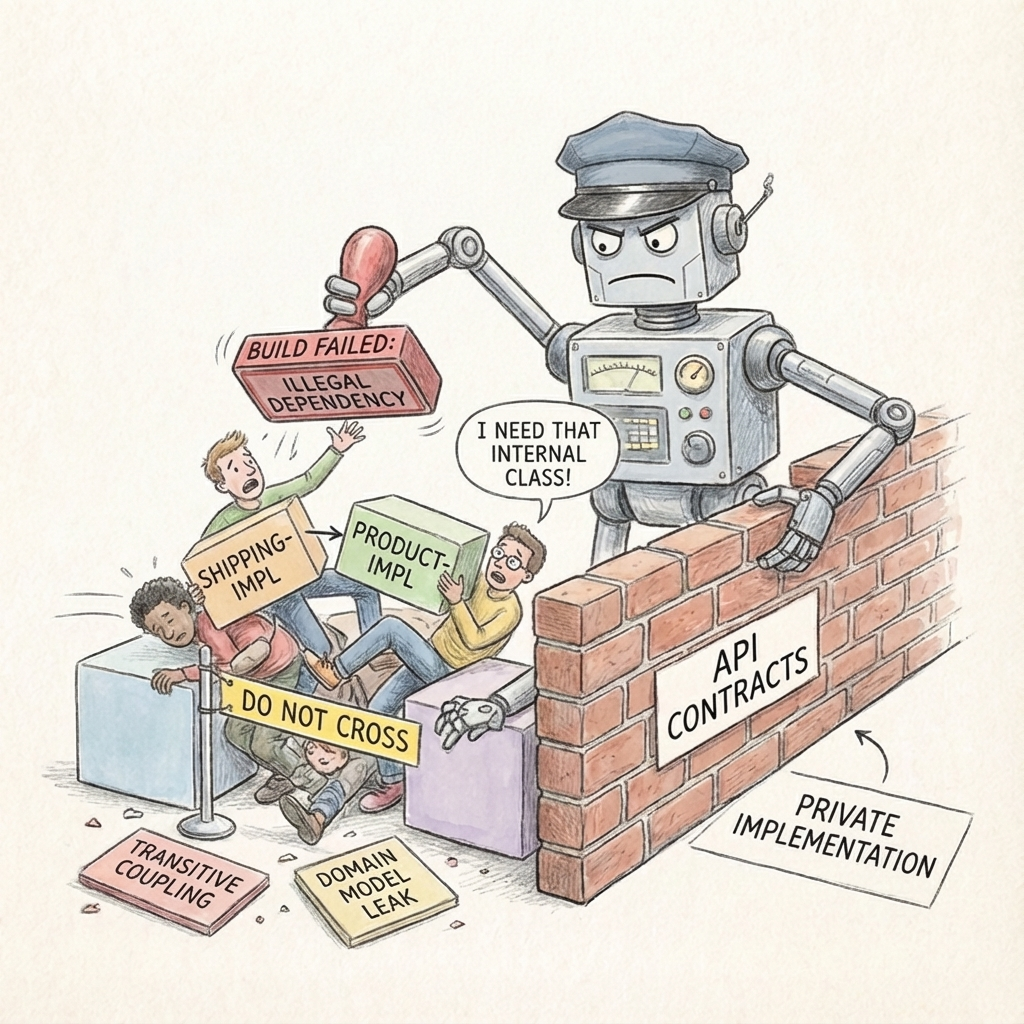

Part 2: Enforcing the Lines

Boundaries on a whiteboard are aspirations. Boundaries in the build system are architecture.

Without enforcement, boundaries erode. It happens slowly, always with good intentions. Someone imports an internal class because it's convenient. Someone adds a "temporary" dependency to meet a deadline. Six months later, your modules are coupled in ways nobody intended, and untangling them is a project of its own.

The solution is to make invalid dependencies a compiler error, not a code review discussion.

Contracts, Not Implementations

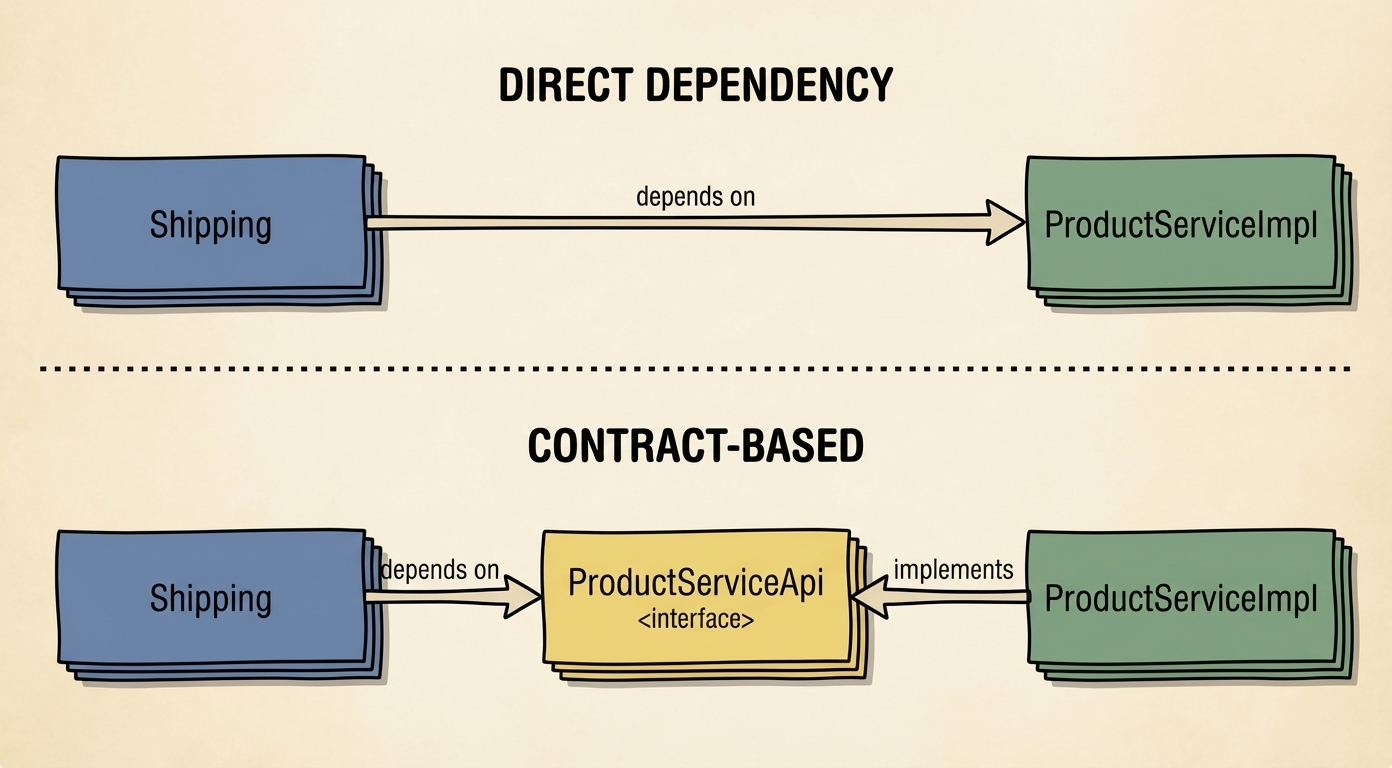

When Shipping needs product information, the obvious approach is to call the Products service directly:

class ShippingService(

private val productService: ProductServiceImpl

) {

fun calculateWeight(productId: ProductId): Grams {

val product = productService.getProduct(productId)

return product.weightGrams

}

}

This works, but it creates tight coupling. Shipping now depends on ProductServiceImpl—a concrete class with its own dependencies, internal structure, and implementation details. And the coupling is transitive: ProductServiceImpl depends on ProductRepository, which depends on database entities. Shipping has indirectly coupled itself to the Products database schema.

The fix is depending on a contract instead of an implementation:

interface ProductServiceApi {

fun getProduct(id: ProductId): ProductDto

}

class ProductServiceImpl(

private val repository: ProductRepository

) : ProductServiceApi {

override fun getProduct(id: ProductId): ProductDto { ... }

}

class ShippingService(

private val productService: ProductServiceApi // Interface, not implementation

) {

fun calculateWeight(productId: ProductId): Grams {

val product = productService.getProduct(productId)

return Grams(product.weightGrams)

}

}

Now Shipping depends on ProductServiceApi—an interface with no implementation details. The Products team can refactor their internals, change their database, swap out libraries. As long as they fulfill the contract, Shipping won't notice.

But where does the contract live? If the interface sits inside the Products module alongside its implementation, Shipping still depends on the Products module. We need to separate the contract into its own place.

The API/Implementation Split

In Gradle, we split each bounded context into two modules:

products/

├── products-api/ # The contract

└── products-impl/ # The implementation

The rules are simple. An -impl module depends on its own -api (it implements the contract). Other modules depend only on -api modules, never on -impl. No circular dependencies.

// shipping-impl/build.gradle.kts

dependencies {

implementation(project(":shipping:shipping-api"))

implementation(project(":products:products-api")) // Contract only

// Cannot add products-impl - that's the whole point

}

If someone tries to import a class from products-impl, the build fails. No discussion needed.

The -api module contains the public contract: interfaces defining what the module can do, DTOs for data exchange, events other modules might listen to, and error types so callers know what can go wrong.

// products-api

interface ProductServiceApi {

fun getProduct(id: ProductId): Result<ProductDto, ProductError>

}

data class ProductDto(

val id: ProductId,

val name: String,

val weightGrams: Int,

)

sealed class ProductError {

data class NotFound(val id: ProductId) : ProductError()

}

The -impl module contains everything private: domain models with business logic, service implementations, persistence layer, controllers. Mark these internal so Kotlin reinforces the boundary:

// products-impl

@Service

internal class ProductServiceImpl(

private val repository: ProductRepository,

) : ProductServiceApi {

// Maps between internal domain model and public DTOs

}

internal data class Product(

val id: ProductId,

val name: String,

val price: Money,

) {

init {

require(name.isNotBlank()) { "Name required" }

}

}

Foreign References

There's a subtle trap when defining contracts. Consider an event that Shipping publishes when a package is delivered:

// shipping-api

data class ShipmentDeliveredEvent(

val shipmentId: ShipmentId,

val orderId: OrderId, // Where does this come from?

)

OrderId lives in orders-api. So shipping-api depends on orders-api. Now if Orders wants to track shipment status and needs ShipmentId, you have a cycle between API modules. Gradle won't compile it.

The instinct is to extract both ID types to a common module. That works initially. Then Inventory needs ProductId. Then Notifications needs CustomerId. Soon your common module contains every ID type in the system, and you've recreated coupling with extra steps.

The fix: each module only defines types it owns. For foreign references, you could use primitives. Or, if you want to prevent passing a shipment id into an order id field by accident, you can create a reference type like OrderReference that is defined locally in the shipping module.

// shipping-api

@JvmInline value class OrderReference(val value: String)

data class ShipmentDeliveredEvent(

val shipmentId: ShipmentId,

val orderReference: OrderReference,

val deliveredAt: Instant,

)

Type safety without coupling. The consuming code converts at the boundary:

// orders-impl

@Component

internal class ShippingEventListener(

private val orderService: OrderService,

) {

fun on(event: ShipmentDeliveredEvent) {

val orderId = OrderId(event.orderReference.value)

orderService.markAsDelivered(orderId, event.deliveredAt)

}

}

This pattern makes sense for Shipping and Orders because they're peers—each might reference the other. But not every relationship is bidirectional. Invoicing is always for an order, but orders never reference invoices. The dependency only flows one way, so invoicing-api can depend on orders-api and use OrderId directly if you are more pragmatic about this.

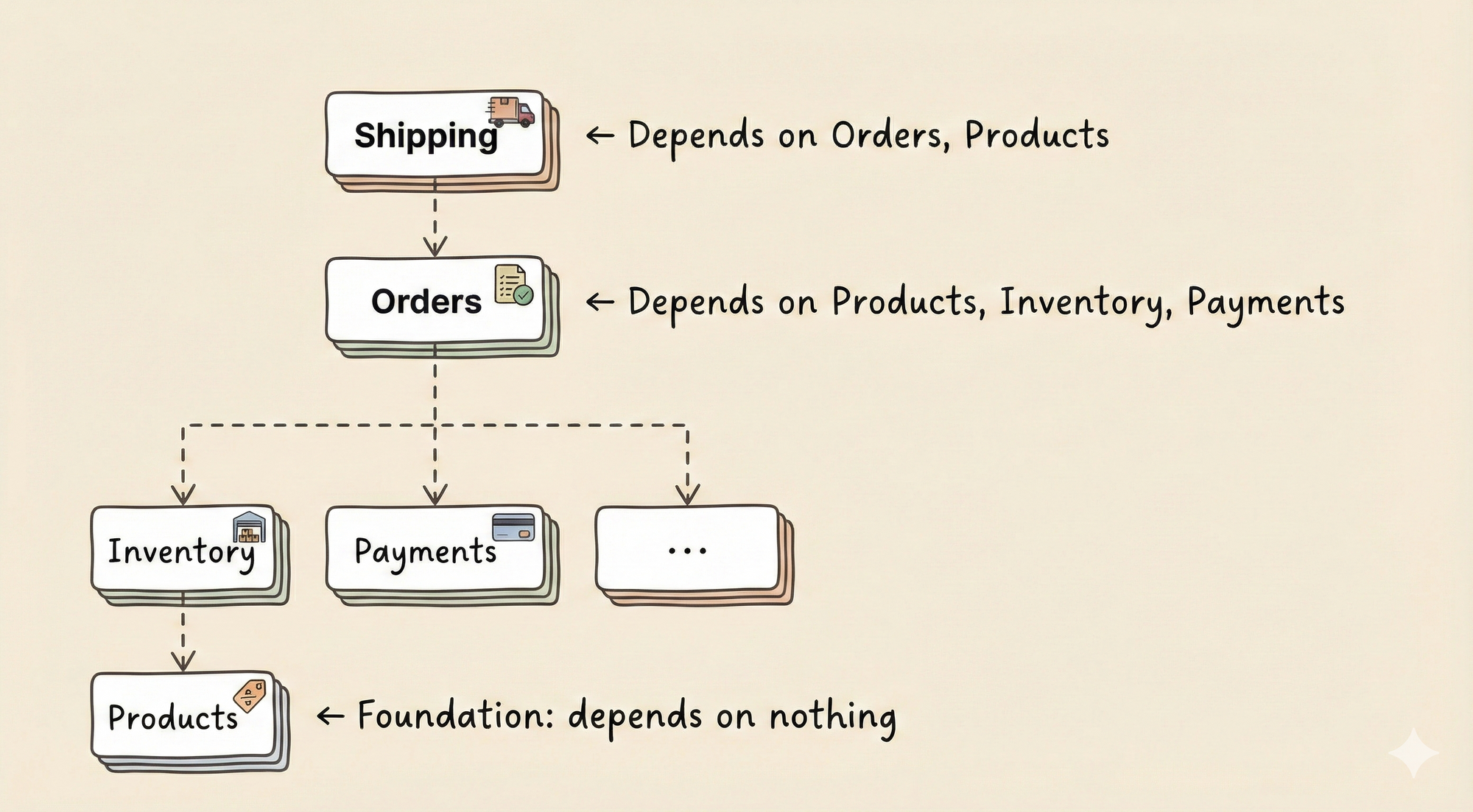

Keeping Bounded Contexts Clean

With primitives at the boundary, you won't hit Gradle cycles. But there's a subtler concern: conceptual pollution.

Products is a foundational module—it defines what you can buy. Orders tracks purchases. Conceptually, Orders needs to know about Products (you order something), but Products shouldn't need to know about Orders. A product exists independently of whether anyone ordered it.

This isn't a technical constraint—with primitives, you could make Products depend on Orders. But you shouldn't. Every dependency accumulates knowledge. When Products depends on Orders, the Products team needs to understand order concepts to work on their module.

Think of modules as layers. Foundational modules at the bottom know nothing about modules above them:

When an arrow would point upward, pause and reconsider. Usually there's an event that could flow the other direction, or an SPI waiting to be extracted.

Service Provider Interfaces

Sometimes a foundational module needs input from higher-level modules without depending on them. Products wants to prevent deletion of a product with pending orders—but shouldn't know about Orders.

The solution is a Service Provider Interface (SPI). Products defines an interface for the question it wants to ask. Other modules provide answers by implementing it.

// products-api/spi/ProductDeletionBlocker.kt

interface ProductDeletionBlocker {

fun canDelete(productId: String): Boolean

}

Orders implements it:

// orders-impl

@Service

internal class OrderBasedDeletionBlocker(

private val orderRepository: OrderRepository

) : ProductDeletionBlocker {

override fun canDelete(productId: String): Boolean {

return !orderRepository.existsPendingForProduct(ProductId(productId))

}

}

Products consumes all implementations without knowing where they come from:

// products-impl

@Service

internal class ProductServiceImpl(

private val repository: ProductRepository,

private val deletionBlockers: List<ProductDeletionBlocker>

) : ProductServiceApi {

fun deleteProduct(id: ProductId): Result<Unit, ProductError> {

if (deletionBlockers.any { !it.canDelete(id.value) }) {

return Err(ProductError.DeletionBlocked)

}

repository.delete(id)

return Ok(Unit)

}

}

Spring collects all beans implementing ProductDeletionBlocker and injects them as a list. Products doesn't know who's blocking or why—it just asks. The knowledge stays where it belongs.

Source Sets Count Too

Gradle projects have test and testFixtures source sets, each with their own dependencies. Each can quietly violate your architecture.

The trap: you create buildProduct() in products-impl:testFixtures. Orders tests need products too, and there's a perfectly good builder right there. So orders-impl:testFixtures depends on products-impl:testFixtures. Now your Orders tests are coupled to Products' internal implementation.

Test fixtures follow the same rules as main code. If a-impl:main can't depend on b-impl:main, then a-impl:testFixtures can't depend on b-impl:testFixtures. The duplication this creates is intentional—each module's test fixtures stay self-contained.

Automated Enforcement

Gradle modules prevent most violations—you can't import what you can't depend on. But some rules need explicit checks, like ensuring no -api module depends on an -impl module, or that test fixtures respect boundaries.

Write a validation task that fails the build on violations, and run it as part of CI. Check the Gradle plugin from the example code: [link]

Architecture enforced by the build system survives deadlines, new team members, and "temporary" workarounds. Architecture enforced by documentation survives until the first Thursday afternoon crunch.

Alternative: Spring Modulith

The Gradle multi-module approach provides the strongest guarantees, but Spring Modulith offers a lighter-weight alternative using package structure and test-time verification.

Spring Modulith treats each top-level package as a module. Classes directly in a module's package are its API; anything in subpackages is internal:

com.example.app/

├── products/

│ ├── ProductService.kt # API - accessible

│ └── internal/ # Internal - hidden

│ └── ProductRepository.kt

└── shipping/

└── ...

A test verifies the structure:

@Test

fun `verify module structure`() {

ApplicationModules.of(Application::class.java).verify()

}

Spring Modulith also provides automatic documentation generation, @ApplicationModuleTest for isolated module testing, and an event publication registry that handles the transactional outbox pattern.

The tradeoff is enforcement timing. Gradle modules reject invalid imports at compile time. Spring Modulith catches them at test time. Stronger guarantees versus easier setup.

You can combine them—use Gradle modules for hard boundaries, add Spring Modulith for its testing and documentation features. Start with your situation: greenfield with clear boundaries favors Gradle modules; existing monolith with unclear boundaries favors Spring Modulith to discover structure first.

Part 3: Inside the Modules

We have modules with enforced boundaries. The build system prevents coupling. The hard part is done.

What happens inside each -impl module matters less now. A mess in one module can't leak into others. You can refactor later without coordinating across teams. Internal structure is a local decision.

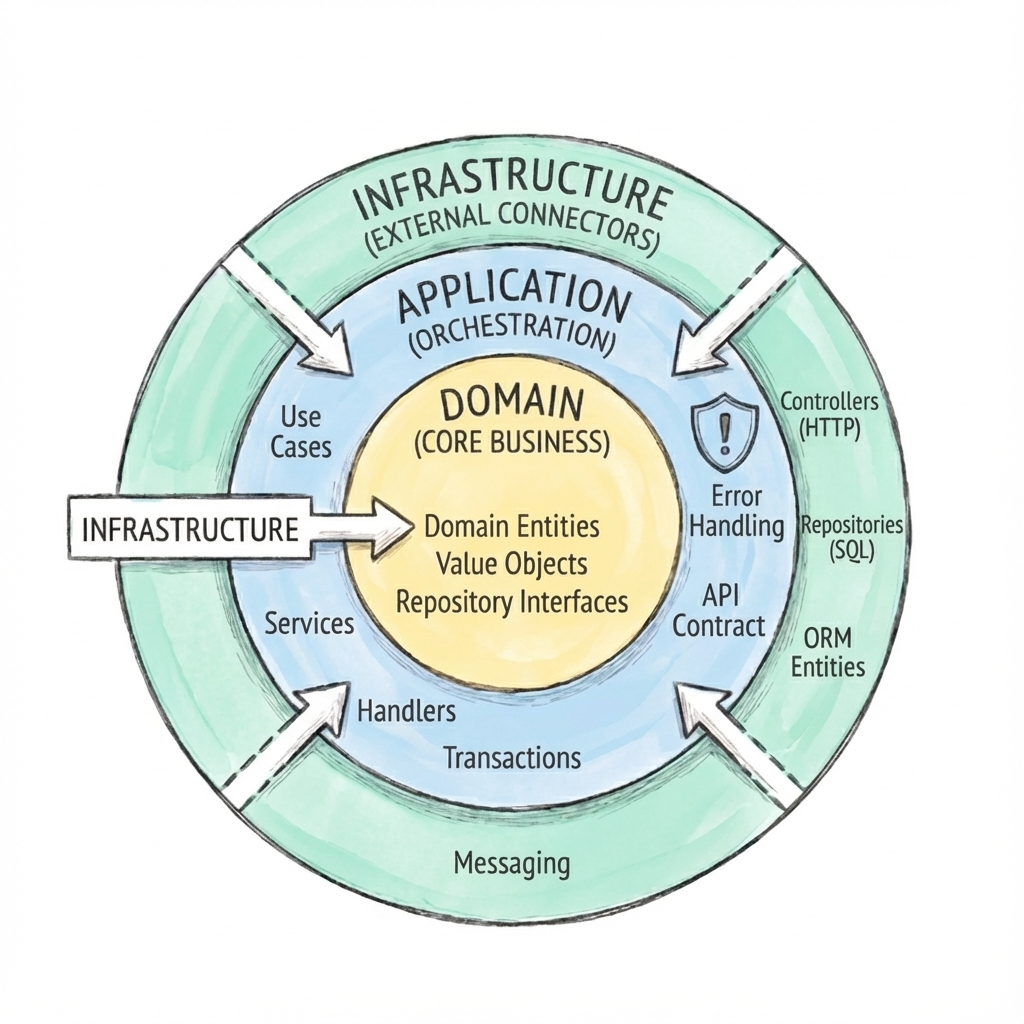

That said, one principle is worth following: dependencies point inward.

The Three Layers

Organize code so that outer layers depend on inner layers, never the reverse.

Domain is the core: business logic, entities, value objects, repository interfaces. No framework dependencies—just plain Kotlin. The domain defines what the system does, not how it connects to the outside world.

Application orchestrates: it implements the API contract, coordinates domain operations, handles transactions, publishes events. Application code uses domain types and repository interfaces but doesn't know about databases or HTTP.

Infrastructure connects to the outside world: controllers, repository implementations, message consumers, external API clients. This is where Spring annotations live, where SQL gets written, where HTTP requests get parsed.

The dependency direction: infrastructure → application → domain. A request flows inward: the controller (infrastructure) calls a handler (application), which uses domain types and a repository interface. The repository implementation (infrastructure) knows how to persist those types—but the domain doesn't know the implementation exists.

This keeps your business logic testable without frameworks and portable across different infrastructure choices. Need to swap Postgres for MongoDB? Only the repository implementation changes. The domain doesn't care.

What Stays Internal

The -api module contains only what other modules actually use. If no other module needs ProductId, it stays in -impl. Don't preemptively publish types "just in case."

That said, value types, enums, and DTOs with simple init validation often do belong in -api. Other modules benefit from knowing they're working with a valid ProductId, not just a String.

// products-api

data class ProductId(val value: String) {

init {

require(value.isNotBlank()) { "ProductId cannot be blank" }

}

}

enum class ProductStatus { DRAFT, ACTIVE, DISCONTINUED }

data class ProductDto(

val id: ProductId,

val name: String,

val status: ProductStatus,

val priceInCents: Long,

)

What stays internal is behavior. Business rules, state transitions, aggregate invariants—the logic that makes your domain more than a data container:

// products-impl

internal data class Product(

val id: ProductId,

val name: String,

val price: Money,

val status: ProductStatus,

) {

fun applyDiscount(percent: Int): Product =

copy(price = price.discountBy(percent))

fun discontinue(): Product {

check(status != ProductStatus.DISCONTINUED) { "Already discontinued" }

return copy(status = ProductStatus.DISCONTINUED)

}

}

internal fun Product.toDto() = ProductDto(

id = id,

name = name,

status = status,

priceInCents = price.toCents(),

)

The rule of thumb: if it's just data and validation, it can be public. If it's behavior, keep it internal.

Organizing Inside the Module

This is less important than it seems. The module boundary protects you—a mess inside one module can't leak into others. Refactor your internal structure whenever you want without coordinating with anyone.

That said, when a module grows multiple features, vertical slices work well. Each feature gets a subpackage with its domain, persistence, messaging, and REST concerns. Shared concepts stay in the module root.

products-impl/

└── src/main/kotlin/com/example/products/

├── Product.kt # Shared domain

├── ProductRepository.kt # Shared persistence

├── ProductServiceFacade.kt # API implementation

├── import/

│ ├── ImportHandler.kt

│ ├── ImportJob.kt

│ ├── persistence/

│ ├── messaging/

│ └── rest/

└── pricing/

├── PricingHandler.kt

├── PriceCalculator.kt

├── persistence/

├── messaging/

└── rest/

When you need to understand pricing, you open one folder. But don't overthink this—pick something reasonable and move on. You can always reorganize later.

Connecting to the API Contract

Other modules depend on the -api interface. A facade delegates to handlers:

@Service

internal class ProductServiceFacade(

private val importHandler: ImportHandler,

private val pricingHandler: PricingHandler,

) : ProductServiceApi {

override fun importProducts(request: ImportRequest) =

importHandler.handle(request)

override fun updatePrice(id: ProductId, request: UpdatePriceRequest) =

pricingHandler.handle(id, request)

}

Pure delegation, no logic. Other modules see one interface; internally, work is split by feature. Controllers inject handlers directly since they're in the same module.

When to Skip All This

Hexagonal architecture and use-case slicing add value when you have complex domain logic that benefits from isolation, multiple entry points (REST, messaging, CLI) to the same operations, or a need to swap infrastructure components.

They add overhead when you're building straightforward CRUD, when the module is small and unlikely to grow, or when you're prototyping and don't know what the domain looks like yet.

Start simple. Add structure when the code tells you it needs it—when you're afraid to touch a class because it does too many things, or when testing requires mocking half the framework. Structure is a response to pain, not a prerequisite.

Part 4: Isolating Data

You can have perfectly separated modules, clean APIs, and enforced dependencies—and still end up with a tightly coupled system. The culprit? The database.

When modules share tables, they share problems. When one module writes directly to another's tables, your boundaries exist only in your imagination. When a foreign key reaches across module boundaries, you've created a dependency that no Gradle configuration can catch.

The Shared Database Trap

It usually starts innocently. The Shipping module needs product weights. Products already has a products table. Why not just join?

-- In shipping code

SELECT s.*, p.weight_grams

FROM shipments s

JOIN products p ON s.product_id = p.id

WHERE s.id = ?

This works. It's fast. It's "just one query."

It's also invisible coupling. Now Shipping depends on the Products table structure. If Products renames weight_grams, Shipping breaks. If Products moves to a different database, Shipping breaks. And nobody sees this dependency in the code—it lurks in SQL strings, waiting to cause an incident during an otherwise routine deployment.

Schema Per Module

The fix is giving each module its own database schema. Products owns the products schema. Shipping owns the shipping schema. The module can only touch tables in its own schema.

CREATE SCHEMA products;

CREATE SCHEMA shipping;

CREATE TABLE products.product (

id VARCHAR(255) PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

weight_grams INT NOT NULL

);

CREATE TABLE shipping.shipment (

id VARCHAR(255) PRIMARY KEY,

product_id VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL, -- Just data, no FK

weight_grams INT NOT NULL -- Copied at creation time

);

Each module gets its own Flyway configuration pointing at its schema. Migrations live with the module code. When there's a problem with the shipments table, there's no ambiguity about who owns it. You can check the example implementation here.

This isn't just convention—configure your repositories to only access their schema, and cross-schema queries become impossible rather than discouraged.

No Foreign Keys Across Schemas

This is the rule that makes people uncomfortable: no foreign keys between schemas.

-- Don't do this

CREATE TABLE shipping.shipment (

id VARCHAR(255) PRIMARY KEY,

product_id VARCHAR(255) REFERENCES products.product(id) -- No!

);

-- Do this instead

CREATE TABLE shipping.shipment (

id VARCHAR(255) PRIMARY KEY,

product_id VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL -- Just a string

);

Referential integrity across module boundaries becomes your responsibility at the application level. When Shipping creates a shipment, it validates that the product exists by calling the Products API:

override fun createShipment(request: CreateShipmentRequest): Result<ShipmentDto, ShipmentError> {

val product = productService.getProduct(request.productId)

.getOrElse { return Err(ShipmentError.ProductNotFound(request.productId)) }

val shipment = Shipment(

id = ShipmentId.generate(),

productId = request.productId,

weightGrams = product.weightGrams,

)

return Ok(shipmentRepository.save(shipment).toDto())

}

Yes, this is more work than a foreign key. But it's explicit—visible in the code, testable, and under your control. And when you eventually need to extract a module into its own service, there are no cross-schema constraints to untangle.

What About Joins?

The most common concern: "I used to join Orders and Products in one query. Now what?"

For single-item lookups, call both services and combine the results. For lists, batch your calls—collect all product IDs first, fetch them in one bulk call, then join in memory:

fun getOrderSummaries(orderIds: List<OrderId>): List<OrderSummary> {

val orders = orderService.getOrders(orderIds)

val productIds = orders.map { it.productId }.distinct()

val products = productService.getProducts(productIds).associateBy { it.id }

return orders.map { order ->

OrderSummary(order, products[order.productId])

}

}

For historical accuracy, denormalize at write time. An order should show the product name and price at the time of purchase, not whatever the product is called today. Copy the relevant fields when creating the order. The data belongs to the order now—it's capturing a moment in time.

For analytics and reporting, pragmatism wins. A read-only reporting schema with cross-module views is fine for dashboards—just keep it separate from your application code.

The Tradeoff

Data isolation requires more code. You lose database-enforced referential integrity across modules. If a product is deleted while a shipment references it, the database won't stop you—your application code has to handle that.

What you get is independence. Products can restructure its tables without Shipping noticing. Module tests can use a real database for their own schema while mocking other modules' APIs. And if you ever extract a module into its own service, the path is clear—no foreign keys to remove, no shared tables to split.

Part 5: Module Communication

Modules need to talk to each other. An order needs product information. A shipment needs to know when payment completes. The question isn't whether modules communicate—it's how they communicate without reintroducing the coupling we worked so hard to eliminate.

Two patterns cover most cases: synchronous calls when you need an answer now, and asynchronous events when you're announcing something happened.

Synchronous Calls

The simplest pattern: one module calls another's API and waits for the response.

@Service

internal class ShipmentServiceImpl(

private val productService: ProductServiceApi,

private val shipmentRepository: ShipmentRepository,

) : ShipmentServiceApi {

override fun createShipment(request: CreateShipmentRequest): Result<ShipmentDto, ShipmentError> {

val product = productService.getProduct(request.productId)

.getOrElse { return Err(ShipmentError.ProductNotFound(request.productId)) }

val shipment = Shipment(

id = ShipmentId.generate(),

productId = request.productId,

weightGrams = product.weightGrams,

status = ShipmentStatus.PENDING,

)

return Ok(shipmentRepository.save(shipment).toDto())

}

}

This is appropriate when you need data to proceed and the operation should fail if the dependency fails. The tradeoff is runtime coupling—if Products is slow, Shipping is slow. For many operations, that's exactly right.

When the external module returns data shaped for their needs rather than yours, translate it at the boundary. Shipping doesn't need product descriptions or images—it needs weight and dimensions. Create an adapter that fetches what you need and discards the rest:

@Component

internal class ProductAdapter(

private val productService: ProductServiceApi

) {

fun getShippableItem(productId: ProductId): ShippableItem? {

val dto = productService.getProduct(productId).getOrNull() ?: return null

return ShippableItem(

id = productId,

weight = Weight.fromGrams(dto.weightGrams),

dimensions = Dimensions(dto.width, dto.height, dto.depth),

isFragile = dto.tags.contains("FRAGILE"),

)

}

}

Now your domain code works with ShippableItem—a type you control—instead of ProductDto which might change when the Products team refactors.

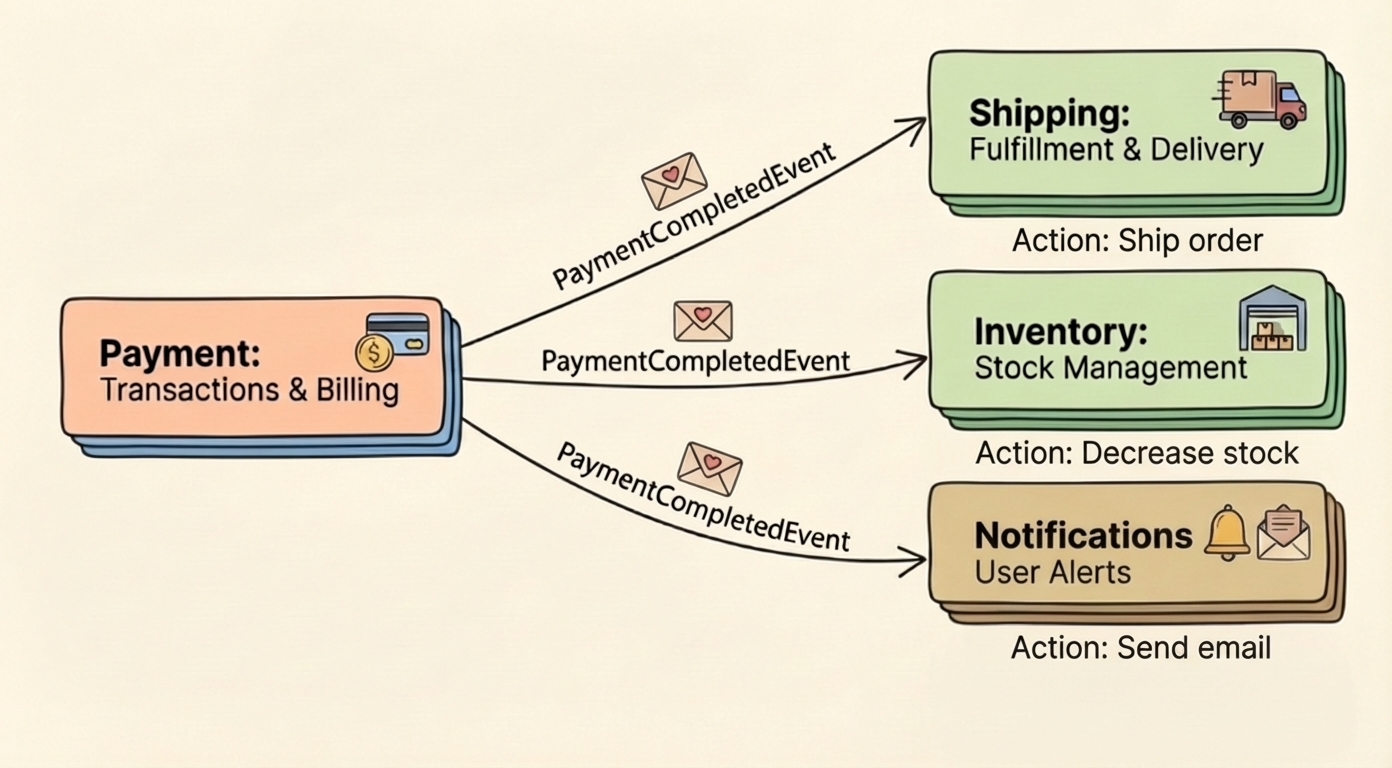

Asynchronous Events

Sometimes a module doesn't need a response. It's announcing that something happened, and other modules react if they care.

// payment-api

data class PaymentCompletedEvent(

val paymentId: String,

val orderReference: String,

val amountInCents: Long,

val currency: String,

val timestamp: Instant,

)

The publisher doesn't know who's listening. Shipping might start fulfillment. Inventory might confirm a reservation. Notifications might send an email. Each listener is independent.

For in-process events, Spring's ApplicationEventPublisher works fine:

@Service

internal class PaymentServiceImpl(

private val eventPublisher: ApplicationEventPublisher,

) : PaymentServiceApi {

@Transactional

override fun completePayment(paymentId: PaymentId): Result<PaymentDto, PaymentError> {

val payment = // ... complete the payment

eventPublisher.publishEvent(PaymentCompletedEvent(

paymentId = payment.id.value,

orderId = payment.orderId.value,

amountInCents = payment.amount.toCents(),

currency = payment.amount.currency.code,

timestamp = Instant.now(),

))

return Ok(payment.toDto())

}

}

Listeners react in their own modules:

// shipping-impl

@Component

internal class PaymentEventListener(

private val shipmentService: ShipmentService,

) {

@TransactionalEventListener(phase = TransactionPhase.AFTER_COMMIT)

fun on(event: PaymentCompletedEvent) {

val orderId = OrderId(event.orderId)

shipmentService.startFulfillment(orderId)

}

}

The AFTER_COMMIT phase ensures the listener only fires if the payment transaction actually commits. No point starting fulfillment for a payment that rolled back.

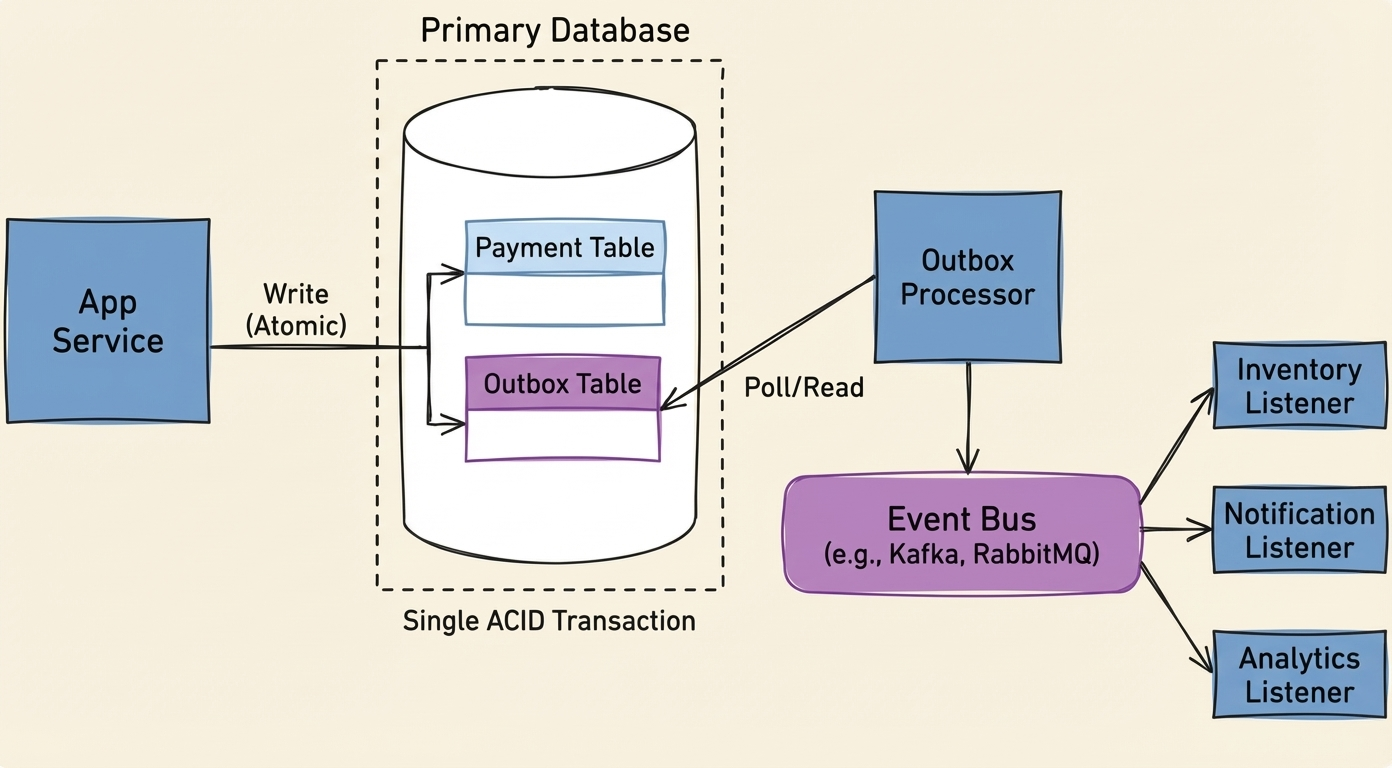

The Dual-Write Problem

There's a subtle issue with publishing events directly. Consider this sequence:

- Update database (payment marked complete)

- Publish event (notify listeners)

- Return success

What if the database write succeeds but event publishing fails? The payment is complete, but nobody knows. Shipping never starts.

What if the event publishes but then the transaction rolls back? Listeners react to something that didn't actually happen.

This is the dual-write problem: updating two systems without a shared transaction.

The solution is making event publishing part of the database transaction, using a transactional outbox. Instead of publishing directly, write the event to an outbox table in the same transaction as your business data.

@Transactional

override fun completePayment(paymentId: PaymentId): Result<PaymentDto, PaymentError> {

val payment = // ... complete the payment

outboxRepository.save(OutboxEvent(

id = EventId.generate(),

type = "PaymentCompleted",

payload = Json.encodeToString(PaymentCompletedEvent(...)),

createdAt = Instant.now(),

))

return Ok(payment.toDto())

}

A separate process polls the outbox and publishes to listeners. If the business transaction rolls back, the outbox entry rolls back too. If it commits, the event is guaranteed to be published eventually.

This guarantees at-least-once delivery. If the publisher crashes after sending but before marking the entry as processed, it republishes on restart. Listeners need to handle duplicates—make them idempotent.

Spring Modulith provides this out of the box with its event publication registry. Add spring-modulith-starter-jpa and events are automatically persisted and retried on failure. Worth considering before building your own.

When to Use What

Most module communication is synchronous calls—simple and direct. Use them when you need data to proceed.

Events handle reactions and loose coupling. Use them when multiple modules might care about something happening, or when the caller shouldn't wait for downstream processing.

The outbox adds reliability when you can't afford to lose events. For in-process events where "probably delivered" is good enough, direct publishing is fine.

The patterns aren't mutually exclusive. A checkout flow might make synchronous calls to validate inventory, write the order and an outbox entry in one transaction, then have listeners react asynchronously to start fulfillment.

Part 6: Errors and Validation

Errors are where modular codebases quietly rot. One team throws exceptions, another returns nulls, a third invents custom result types. The controller layer becomes a graveyard of catch blocks trying to translate chaos into HTTP status codes.

Make Errors Explicit

The traditional approach:

fun getProduct(id: ProductId): Product {

return repository.findById(id)

?: throw ProductNotFoundException(id)

}

Nothing in the type signature hints that this might throw. You discover ProductNotFoundException exists when it crashes in production—or if you're lucky, by reading documentation that probably doesn't exist.

But "product not found" isn't exceptional. It's a normal business case—the user typed a wrong ID, the product was deleted. This happens all the time, and the code should make it obvious.

Return errors as values instead. Define them in the -api module using sealed classes:

// products-api

sealed class ProductError {

data class NotFound(val id: ProductId) : ProductError()

data class InvalidData(val reason: String) : ProductError()

data object DuplicateName : ProductError()

}

interface ProductServiceApi {

fun getProduct(id: ProductId): Result<ProductDto, ProductError>

fun createProduct(request: CreateProductRequest): Result<ProductDto, ProductError>

}

Now the type signature tells you everything. And because ProductError is sealed, the compiler knows all possible cases. Add a new error type and every call site that doesn't handle it becomes a compile error.

// products-impl

@Service

internal class ProductServiceImpl(

private val repository: ProductRepository,

) : ProductServiceApi {

override fun getProduct(id: ProductId): Result<ProductDto, ProductError> {

val product = repository.findById(id)

?: return Err(ProductError.NotFound(id))

return Ok(product.toDto())

}

}

Callers handle both cases explicitly:

productService.getProduct(productId).fold(

onSuccess = { product -> /* use it */ },

onFailure = { error -> /* handle it */ }

)

No try-catch. No wondering what might throw.

A note on Result types: Kotlin's built-inResultonly supportsThrowableas the error type—it can't model domain errors. You need a proper either type withOkandErrvariants. The example project includes a simple implementation, or use kotlin-result or Arrow's Either. Pick one and use it everywhere.

Validation in Init Blocks

Where should validation live? The traditional answer in Spring is JSR-303 annotations—@NotBlank, @Positive, @Valid. It works, but scatters validation rules across annotations that are easy to miss and harder to test than plain code.

A better approach: validate at construction time. If an object exists, it's valid. This follows the "Parse, don't validate" principle—your init blocks act as a firewall, preventing garbage data from ever entering your implementation layer.

Kotlin gives you require for validating inputs and check for validating state. Both throw on failure, but they signal different problems. require throws IllegalArgumentException—the caller passed bad input. check throws IllegalStateException—something is wrong internally.

Structural vs. Business Validation

Not all validation belongs in the same place:

| Type | Definition | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Structural | Checks data against itself. No external context needed. (e.g., "Quantity > 0", "Name not blank") | API Module (init block) |

| Business | Checks data against state or rules. Needs database or config. (e.g., "Email is unique", "Product in stock") | Implementation Module (Service) |

Structural validation in API modules works well: exceptions fire immediately during deserialization, the code documents requirements for consumers, and your domain logic doesn't need defensive null checks everywhere.

// orders-api

data class CreateOrderRequest(

val customerId: String,

val items: List<OrderItemDto>,

) {

init {

require(customerId.isNotBlank()) { "Customer ID is required" }

require(items.isNotEmpty()) { "Order must contain at least one item" }

}

}

data class OrderItemDto(

val productId: String,

val quantity: Int

) {

init {

require(productId.isNotBlank()) { "Product ID is required" }

require(quantity > 0) { "Quantity must be positive" }

}

}

Avoid encoding volatile rules in the API. require(password.isNotEmpty()) is fine; require(password.length >= 10) couples your contract to a policy that might change. Check specific length requirements in the service layer.

For internal domain objects, use check:

// products-impl

internal data class Product(

val id: ProductId,

val name: String,

val price: Money,

) {

init {

check(name.isNotBlank()) { "Product name cannot be blank" }

check(name.length <= 200) { "Product name too long" }

}

}

If these fail, it means your application code tried to create an invalid domain object—a bug, not bad user input.

Translating Errors to HTTP

The domain layer doesn't know about HTTP. It returns ProductError.NotFound. Somewhere, that needs to become a 404.

That translation happens at the controller:

@RestController

internal class ProductController(

private val productService: ProductServiceApi,

) {

@GetMapping("/products/{id}")

fun getProduct(@PathVariable id: ProductId): ResponseEntity<ProductDto> {

return productService.getProduct(id).fold(

onSuccess = { ResponseEntity.ok(it) },

onFailure = { throw it.toResponseStatusException() }

)

}

}

fun ProductError.toResponseStatusException() = when (this) {

is ProductError.NotFound -> ResponseStatusException(NOT_FOUND, "Product not found: $id")

is ProductError.InvalidData -> ResponseStatusException(BAD_REQUEST, reason)

is ProductError.DuplicateName -> ResponseStatusException(CONFLICT, "Product name already exists")

}

Spring Boot converts ResponseStatusException to RFC 7807 Problem Details automatically. The domain stays clean. The HTTP translation is explicit and in one place. When you add a new error type, the when expression forces you to decide what HTTP status it maps to.

A global exception handler deals with the init block validations:

@RestControllerAdvice

class GlobalExceptionHandler {

@ExceptionHandler(IllegalArgumentException::class)

fun handleBadInput(ex: IllegalArgumentException): ProblemDetail {

return ProblemDetail.forStatusAndDetail(

HttpStatus.BAD_REQUEST,

ex.message ?: "Invalid request"

)

}

@ExceptionHandler(IllegalStateException::class)

fun handleInternalError(ex: IllegalStateException): ProblemDetail {

// Log it - this is a bug

return ProblemDetail.forStatusAndDetail(

HttpStatus.INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR,

"Something went wrong"

)

}

}

When Exceptions Are Still Fine

This doesn't mean exceptions are always wrong. Use them for genuinely exceptional situations: database connection lost, file system full, external service unreachable. These aren't business cases your callers should handle individually—they're infrastructure failures that bubble up to a global handler.

The distinction: if the caller can reasonably do something about it, return a Result. If it's an unexpected failure that should abort the operation, throw

Part 7: Testing

A modular architecture should make testing easier, not harder. If you need to spin up the entire application to test whether a discount calculation works, something has gone wrong.

The module boundaries we've enforced create natural test boundaries. Each module has a clear API and explicit dependencies. This suggests a strategy: test one module completely, mock the others.

Module Tests

The Shipping module depends on ProductServiceApi, not ProductServiceImpl. In tests, provide a mock and test Shipping in isolation—real database, real transactions, real queries—without Products existing at all.

Gherkin works well for expressing what a module should do:

Feature: Shipment Creation

Scenario: Create shipment for valid product

Given a product "PROD-123" with weight 500 grams

When I create a shipment for product "PROD-123" to "123 Main St"

Then the shipment should be created with weight 500 grams

And the shipment status should be "PENDING"

Scenario: Fail when product does not exist

Given no product "UNKNOWN" exists

When I create a shipment for product "UNKNOWN" to "123 Main St"

Then the shipment should fail with "ProductNotFound"

The step definitions mock external modules. "Given a product exists" doesn't create a real product—it stubs the mock to return one:

class ShipmentSteps(

private val shippingService: ShippingServiceApi,

private val productService: ProductServiceApi, // Mocked

) {

private var result: Result<ShipmentDto, ShipmentError>? = null

@Given("a product {string} with weight {int} grams")

fun givenProduct(productId: String, weight: Int) {

whenever(productService.getProduct(ProductId(productId)))

.thenReturn(Ok(buildProductDto(id = ProductId(productId), weightGrams = weight)))

}

@When("I create a shipment for product {string} to {string}")

fun createShipment(productId: String, address: String) {

result = shippingService.createShipment(

CreateShipmentRequest(productId = ProductId(productId), address = address)

)

}

@Then("the shipment should be created with weight {int} grams")

fun verifyWeight(expectedWeight: Int) {

assertThat(result?.value?.weightGrams).isEqualTo(expectedWeight)

}

}

When a module test fails, you know which module broke. When it passes, you have confidence the module actually fulfills its contract against a real database. These are often your highest-value tests—fast enough to run frequently, realistic enough to catch real bugs.

Unit and Repository Tests

Module tests cover most scenarios, but some things deserve focused tests.

Complex logic that doesn't need a database—calculations, state machines, validation rules—these are faster to test in isolation:

class MoneyTest {

@Test

fun `discount reduces amount correctly`() {

val money = Money(BigDecimal("100"), EUR)

assertThat(money.discountBy(20).amount).isEqualByComparingTo(BigDecimal("80"))

}

}

Complex queries where the logic lives in SQL also deserve their own tests. Filters, pagination, edge cases with NULL values—these are hard to get right and easy to break. Use Testcontainers to test against a real Postgres. Don't use H2 "because it's faster"—it behaves differently in ways that will bite you.

@DataJdbcTest

@Import(FlywayConfig::class)

class ProductRepositoryTest {

companion object {

@Container

@ServiceConnection

val postgres = PostgreSQLContainer("postgres:15")

}

@Autowired

private lateinit var repository: ProductRepository

@Test

fun `finds products by category with price range`() {

// Given

repository.save(buildProduct(category = "electronics", priceInCents = 5000))

repository.save(buildProduct(category = "electronics", priceInCents = 15000))

repository.save(buildProduct(category = "clothing", priceInCents = 3000))

// When

val results = repository.findByCategoryAndPriceRange(

category = "electronics", minPrice = 1000, maxPrice = 10000

)

// Then

assertThat(results).hasSize(1)

assertThat(results.first().priceInCents).isEqualTo(5000)

}

}

If a method just does findById or delegates to a repository and maps the result, skip the dedicated test—the module test already covers it.

Application-Level Tests

Sometimes you need to verify the full flow—all modules wired together, real database, real event publishing. Save these for critical user journeys where integration failures would be costly.

Feature: Checkout

Scenario: Complete purchase creates order and schedules shipment

Given I am logged in as a customer

And a product "Widget" priced at €29.99

And the product is in stock

When I place an order for 1 "Widget"

Then an order should be created

And a shipment should be scheduled with status "PENDING"

The step definitions wire this to real services—no mocks. These tests are slow and brittle. When they fail, the cause isn't always obvious. Write few of them and let module tests handle the detailed behavior.

Test Fixtures

Tests need data. You don't want every test constructing objects from scratch, but you also don't want shared fixtures that create invisible dependencies between tests.

Builder functions with default arguments hit the sweet spot:

fun buildProductDto(

id: ProductId = ProductId(UUID.randomUUID().toString()),

name: String = "Test Product",

weightGrams: Int = 100,

) = ProductDto(id = id, name = name, weightGrams = weightGrams)

// Only specify what matters for this test

val lightweight = buildProductDto(weightGrams = 50)

When you read a test that says buildProductDto(weightGrams = 500), you know the weight matters. Everything else is scaffolding.

Keep fixtures independent across modules. Shipping tests mock ProductServiceApi and use buildProductDto() from the -api test fixtures. They don't reach into Products' internal test helpers. The same boundary rules apply to test code.

Test Behavior, Not Implementation

Ask "what should happen" rather than "how does it happen internally."

// Good - tests outcome

@Test

fun `order fails when product is out of stock`() {

whenever(inventoryService.checkAvailability(productId, quantity = 5))

.thenReturn(Available(inStock = 3))

val result = orderService.createOrder(CreateOrderRequest(productId, quantity = 5))

assertThat(result.error).isEqualTo(OrderError.InsufficientStock(available = 3))

}

// Brittle - tests mechanics

@Test

fun `createOrder calls inventory then repository then publisher`() {

orderService.createOrder(request)

inOrder(inventoryService, orderRepository, eventPublisher).apply {

verify(inventoryService).checkAvailability(any(), any())

verify(orderRepository).save(any())

verify(eventPublisher).publishEvent(any())

}

}

The first test survives refactoring. Reorder the internal calls, add caching, change how you publish events—the test still passes because the behavior is the same. The second test breaks the moment you touch the implementation, even if nothing is actually wrong.

Don't chase coverage numbers. A codebase with 70% coverage and thoughtful tests beats one with 95% coverage and useless tests. Coverage tells you what code ran, not whether your tests would catch a bug.

Part 8: Putting It All Together

We've covered modules, boundaries, data isolation, communication, errors, and testing. How does it actually become a running application?

The good news: it's simpler than you might expect. One application module pulls in the implementations, Spring wires them together, and you deploy a single JAR.

The Application Module

The application module is the composition root—the place where all the pieces come together. Its build.gradle.kts depends on all the -impl modules:

// application/build.gradle.kts

dependencies {

implementation(project(":products:products-impl"))

implementation(project(":orders:orders-impl"))

implementation(project(":shipping:shipping-impl"))

implementation(project(":inventory:inventory-impl"))

// Spring Boot, database drivers, etc.

implementation("org.springframework.boot:spring-boot-starter-web")

implementation("org.postgresql:postgresql")

}

This is the only place that depends on -impl modules. Everyone else depends on -api modules. The application module breaks that rule because its job is to assemble everything.

The application class itself is just a standard Spring Boot entry point:

@SpringBootApplication(scanBasePackages = ["com.example"])

class Application

fun main(args: Array<String>) {

runApplication<Application>(*args)

}

The scanBasePackages needs to cover your root namespace so Spring discovers components in all your -impl modules.

How Spring Wires It

A common question: if ShippingServiceImpl needs ProductServiceApi, and they're in different Gradle modules, how does Spring connect them?

Spring doesn't care about Gradle modules—it cares about the classpath. When the application starts, all the -impl modules are on the classpath. Spring scans for components, finds ProductServiceImpl (which implements ProductServiceApi), and registers it as a bean. When it creates ShippingServiceImpl, it sees a constructor parameter of type ProductServiceApi, finds the matching bean, and injects it.

// products-impl

@Service

internal class ProductServiceImpl(...) : ProductServiceApi

// shipping-impl

@Service

internal class ShippingServiceImpl(

private val productService: ProductServiceApi // Spring injects ProductServiceImpl

) : ShippingServiceApi

The interface is public (in -api). The implementation is internal (in -impl). Spring wires them together because at runtime, they're all in the same application context.

This is one of the key benefits of a modular monolith over microservices—no service discovery, no HTTP clients, no serialization overhead. Just dependency injection.

Project Structure

The overall structure follows naturally from what we've covered:

project-root/

├── build-logic/ # Shared Gradle conventions

│ └── src/main/kotlin/

│ └── kotlin-conventions.gradle.kts

├── common/

│ ├── common-types/ # Shared value types

│ └── common-result/ # Result type

├── products/

│ ├── products-api/

│ └── products-impl/

├── orders/

│ ├── orders-api/

│ └── orders-impl/

├── shipping/

│ ├── shipping-api/

│ └── shipping-impl/

├── application/ # Composition root

└── settings.gradle.kts

The build-logic module contains convention plugins that centralize shared Gradle configuration. Instead of repeating Kotlin version, test configuration, and dependencies in every build.gradle.kts, modules apply a plugin like id("kotlin-conventions"). Change the convention once, every module picks it up.

Use gradle/libs.versions.toml to manage dependency versions in one place:

[versions]

kotlin = "2.0.21"

spring-boot = "3.4.1"

testcontainers = "1.20.4"

[libraries]

spring-boot-starter-web = { module = "org.springframework.boot:spring-boot-starter-web", version.ref = "spring-boot" }

spring-boot-starter-data-jdbc = { module = "org.springframework.boot:spring-boot-starter-data-jdbc", version.ref = "spring-boot" }

testcontainers-postgres = { module = "org.testcontainers:postgresql", version.ref = "testcontainers" }

[plugins]

kotlin-jvm = { id = "org.jetbrains.kotlin.jvm", version.ref = "kotlin" }

spring-boot = { id = "org.springframework.boot", version.ref = "spring-boot" }

Then in any module:

dependencies {

implementation(libs.spring.boot.starter.web)

testImplementation(libs.testcontainers.postgres)

}

No more version strings scattered across dozens of build.gradle.kts files. Update a version once in the TOML, and every module picks it up.

Running It

The Spring Boot plugin packages everything into a single executable JAR. Run ./gradlew :application:bootJar and you get one artifact containing all modules, all dependencies, and an embedded server. Deploy it anywhere that runs Java.

For local development, you typically need a database. A simple Docker Compose handles that:

services:

postgres:

image: postgres:15

environment:

POSTGRES_DB: app

POSTGRES_USER: app

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: app

ports:

- "5432:5432"

Start the container, run ./gradlew :application:bootRun, and you're developing.

When You Outgrow It

The architecture is designed to be "split-ready," even if you never split.

If a module eventually needs to become a separate service, the path is clear. The database is already isolated—each module has its own schema, so you export it to a new database without untangling shared tables. The API is already defined—the -api module becomes the contract for the new service, and you replace the in-process implementation with an HTTP client. Communication is already explicit—you swap dependency injection for network calls. Tests are already structured—module tests that mocked ProductServiceApi now mock the HTTP client instead.

You're not refactoring a tangled mess. You're promoting a module that's already isolated.

Most teams never need to do this. The modular monolith scales further than people expect—both technically and organizationally. Multiple teams can work on different modules without stepping on each other, and the single deployment model remains manageable well into hundreds of thousands of lines of code.

But knowing the escape hatch exists makes the choice less risky. You're not betting everything on a monolith forever. You're choosing the simplest architecture that works today while keeping your options open.

Conclusion

A modular monolith isn't a compromise or a stepping stone to microservices. For most teams, it's the destination.

You get boundaries that hold—not because everyone remembered the guidelines, but because the compiler enforces them. You get changes that stay local, because modules can't reach into each other's internals. You get deployment that stays simple, because it's still one JAR, one process, one thing to monitor at 3am when something goes wrong.

Not everything in this guide carries equal weight. Some things are load-bearing: enforcement through Gradle modules, the API/implementation split, data isolation. Skip these, and the "modular" part of your monolith will erode within months. Other things—how you organize packages inside a module, whether you use Cucumber, what you name your handlers—are local decisions. Get them wrong and you have a mess, but it's a contained mess. The module boundary limits the blast radius.

That's the real payoff. In a traditional monolith, every shortcut becomes everyone's problem. In a modular monolith, a messy module is just a messy module. Clean it up later, on your own schedule, without coordinating across teams.

Build the boundaries. Enforce them. Ship the JAR.

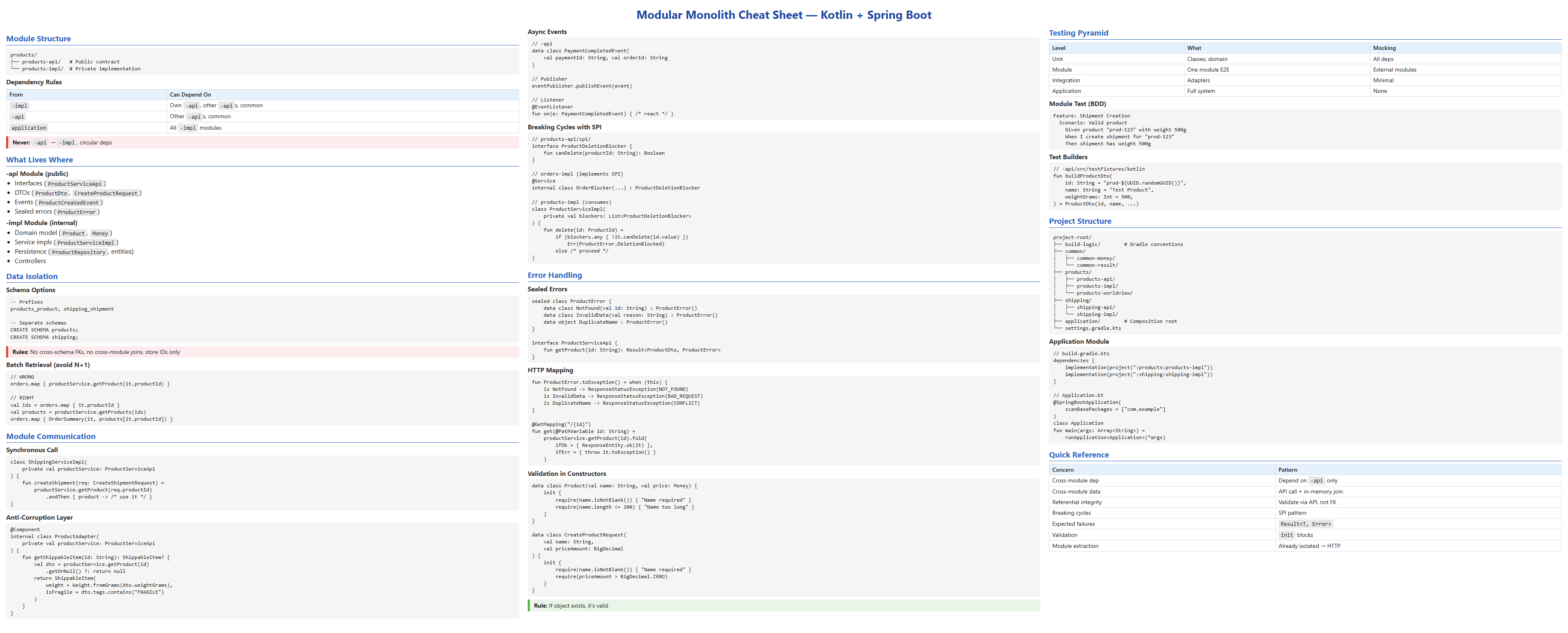

Finally, a cheat sheet as quick reference: